Australia was once home to many gigantic animals - megafauna - whose existence probably coincided with the arrival of humans.

New research from Flinders University has now revealed how those animals might have died out.

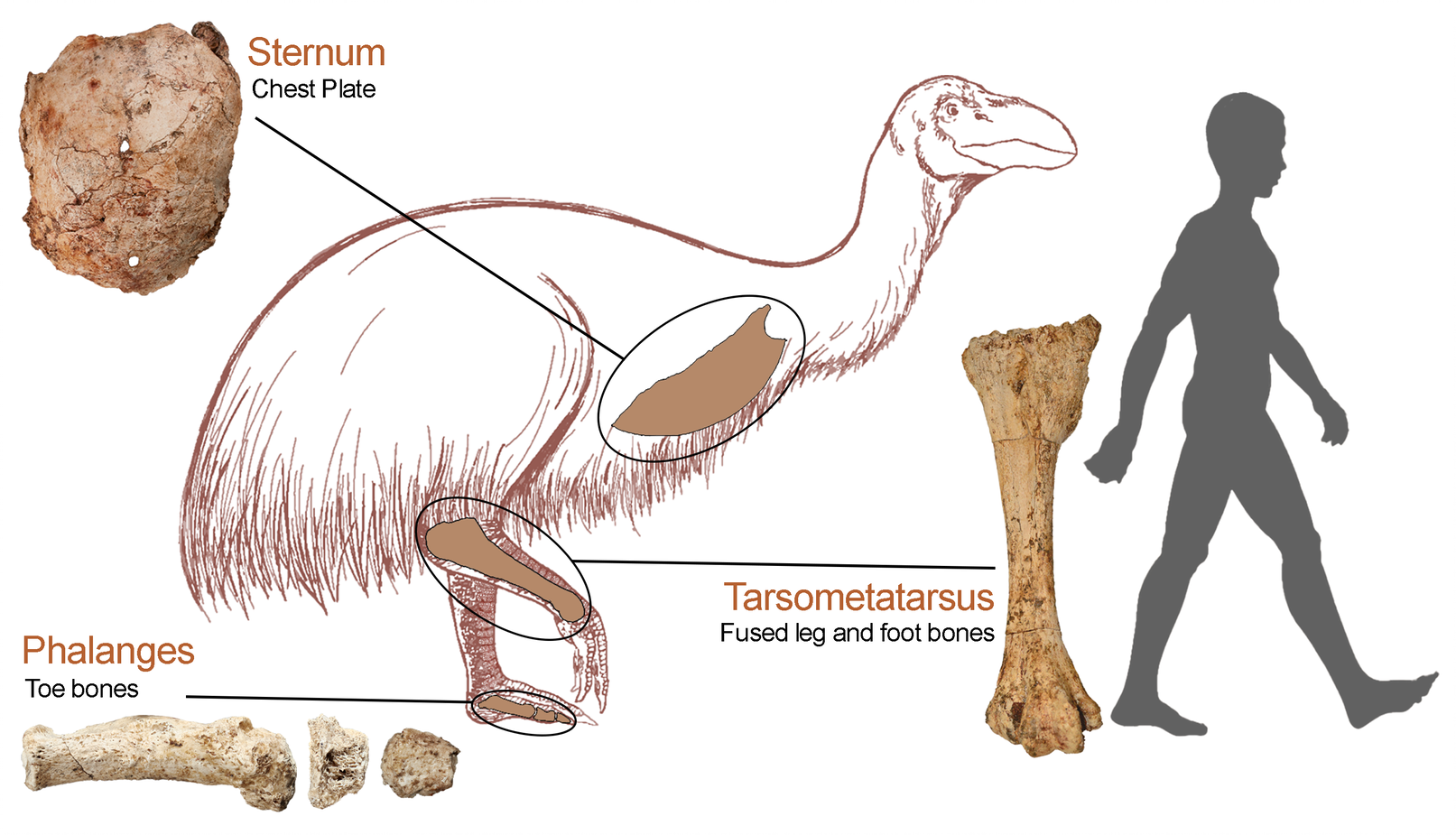

A rare fossil discovery in South Australia in particular focused attention on the fate of the dromornithids, the "thunder birds" (Genyornis newtoni).

LIVE UPDATES: Third Newcastle nightspot triggers Omicron alert

Research published in the journal Papers in Palaeontology, revealed that several Genyornis fossils showed severe bone infections.

Lead author Phoebe McInerney said the condition would have hampered the birds' mobility and foraging.

"The fossils with signs of infection are associated with the chest, legs and feet of four individuals," she said.

"They would have been increasingly weakened, suffering from pain, making it difficult to find water and food."

READ MORE: COVID-19 shuts down Australian Netflix production

The remains were found in the salt beds of Lake Callabonna, about 600km north-east of Adelaide.

The giant Genyornis weighed around 230kg – five to six times that of an emu – and stood about two metres tall.

The study found about 11 per cent of the birds were suffering from osteomyelitis, a severe bone infection.

University of Adelaide co-author, Associate Professor Lee Arnold, dated the lake sediments in which Genyornis was found. This linked the deaths of these individuals with a period of severe drought beginning about 48,000 years ago.

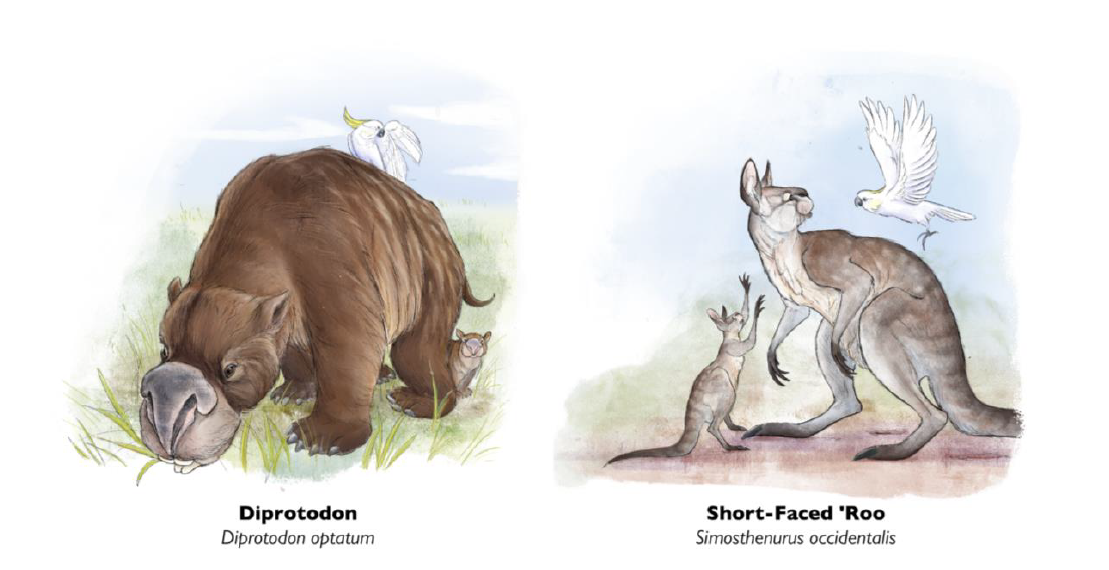

During this drought, these giant birds, along with other megafaunal species, including the ancient giant relatives of the wombats and kangaroos, were facing major environmental challenges.

READ MORE: CCTV shows shooter open fire outside Sydney gym

As the landscape dried across Australia, the large inland lakes and forests began to disappear, and central Australia became flat desert plains now covered by lakes of salt.

"As the drought conditions worsened, food resources would have been reduced, placing considerable stress on the animals", says co-author Associate Professor Trevor Worthy, from Flinders University's Palaeontology Laboratory.

"From studies on living birds, we know that challenging environmental conditions can have negative physiological effects, so we infer that the Lake Callabonna population of Genyornis would have been struggling through such conditions."

With no conclusive evidence to suggest that Genyornis newtoni survived much past this time, it is likely that protracted drought and high disease rates may have contributed to this species eventual extinction.

At another fossil site, the Naracoorte Caves in South Australia, modelling suggested changes to Australian plantlife, brought about by human land use and climate change, could have contributed to the extinction of ancient plant eaters such as Diprodoton.

READ MORE: Mystery lump from woman's bushwalk ends in her hospitalisation

The study was published in the journal Ecography.

"By modelling the ecological community using powerful computing methods, we can simulate any extinct or modern species' relative position in the overall food chain as it existed many millennia ago, and then estimate how vulnerable these species were to changes in the ecosystem," says Flinders University evolutionary ecologist and lead author Dr John Llewelyn.

"Our models revealed that extinct species of megafauna, particularly the big plant eaters, were more vulnerable to these 'bottom-up' coextinction cascades triggered by changes in plant species than were the species that we still have around today."

The analyses also showed that species lower on the food chain, such as plant eaters that specialised on only a few plant species for food, were particularly vulnerable.