Like many people, historian A. Roger Ekirch thought that sleep was a biological constant - and eight hours of rest a night never really varied over time and place.

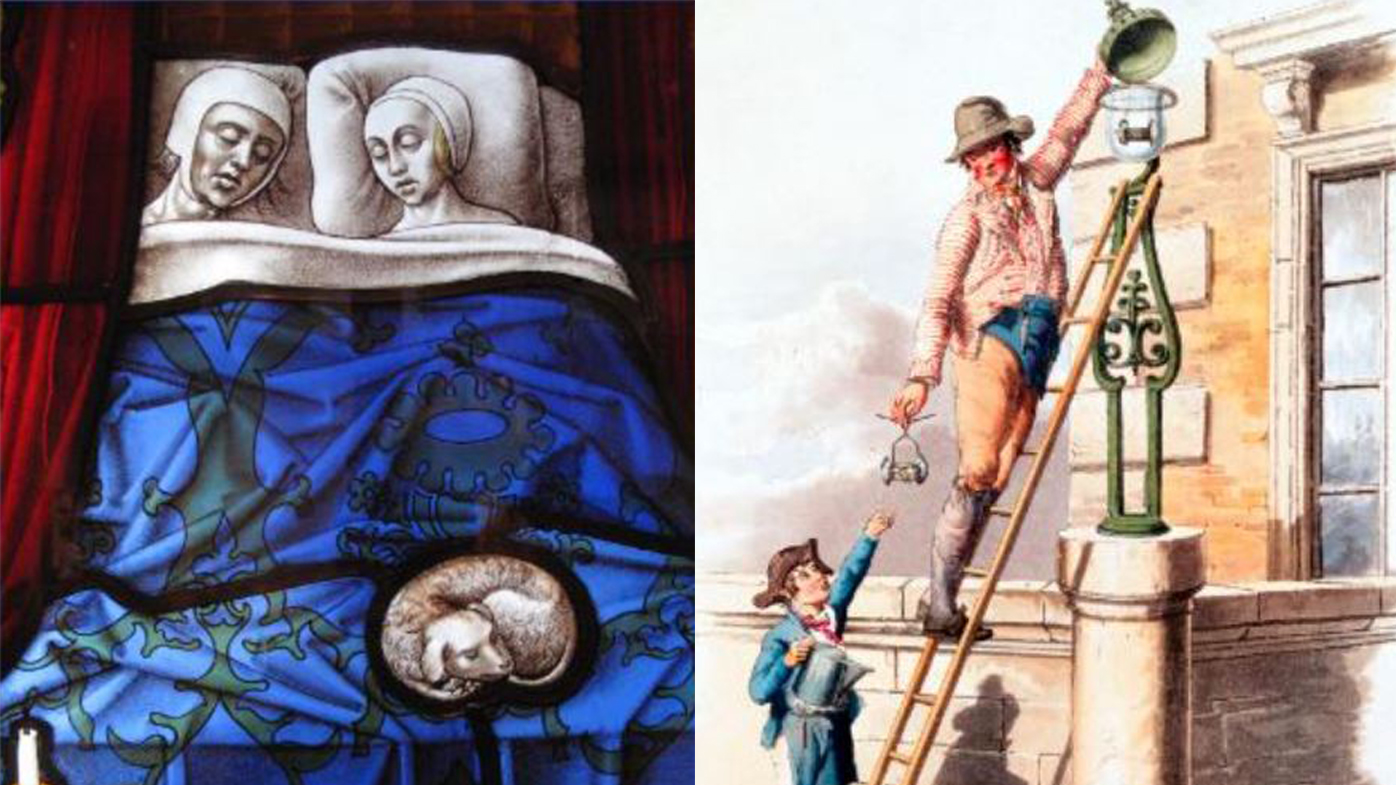

But while researching nocturnal life in pre-industrial Europe and the US, he discovered the first evidence that many humans used to sleep in segments - a first sleep and second sleep with a break of a few hours in between to have sex, pray, eat, chat and take medicine.

"Here was a pattern of sleep unknown to the modern world," Professor Ekirch, from the department of history at Virginia Tech, said.

LIVE UPDATES: Half a million Aussies have COVID-19

READ MORE: Djokovic faces visa court battle to stay in Australia

Professor Ekirch's subsequent book, "At Day's Close: Night in Times Past," unearthed more than 500 references to what's since been termed biphasic sleep.

He has now found more than 2000 references in a dozen languages and going back in time as far as ancient Greece.

His 2004 book will be republished in April.

The practice of sleeping through the whole night didn't really take hold until just a few hundred years ago, Professor Ekirch's work suggested.

It only evolved thanks to the spread of electric lighting and the Industrial Revolution, with its capitalist belief that sleep was a waste of time that could be better spent working.

The history of sleep not only reveals fascinating details about everyday life in the past, but the work of Professor Ekirch, and other historians and anthropologists, is helping sleep scientists gain fresh perspective on what constitutes a good night's sleep.

It also offers new ways to cope with and think about sleep problems.

There is value in knowing about this prior pattern of sleep in the Western world.

"A large number of people who today suffer from middle-of-the-night insomnia, the primary sleep disorder in the US - and I dare say in most industrialised countries - rather than experiencing a quote unquote, disorder, are in fact, experiencing a very powerful remnant, or echo of this earlier pattern of sleep," Professor Ekirch said.

READ MORE: Nineteen dead in 'unprecedented' New York fire disaster

Myth of eight-hour sleep?

The first reference to biphasic sleep Professor Ekirch found was in a 1697 legal document from a traveling "Assizes" court buried in a London record office.

The deposition of a nine-year-old girl called Jane Rowth mentioned that her mother awoke after her "first sleep" to go out. The mother was later found dead.

"I had never heard the expression, and it was expressed in such a way that it seemed perfectly normal," he said.

"I then began to come across subsequent references in these legal depositions but also in other sources."

Professor Ekirch subsequently found multiple references to a "first" and "second" sleep in diaries, medical texts, works of literature and prayer books.

A doctor's manual from 16th century France advised couples that the best time to conceive was not at the end of a long day but "after the first sleep," when "they have more enjoyment" and "do it better."

By the early 19th century, however, the first sleep had begun to expand at the expense of the second sleep, Professor Ekirch found, and the intervening period of wakefulness.

By the end of the century, the second sleep was little more than turning over in one's bed for an extra 10 minutes of snoozing.

Ben Reiss, author of "Wild Nights: How Taming Sleep Created Our Restless World" and professor and chair of the English department at Emory University in Atlanta, blames the Industrial Revolution and the "sleep is for wimps" attitude it engendered.

"The answer is really to follow the money. Changes in economic organisation, when it became more efficient to routinise work and have large numbers of people showing up on factory floors, at the same time and doing as much work in as concentrated fashion as possible," Professor Reiss said.

He said our sleep schedule got squeezed and consolidated as a result.

READ MORE: Turkmenistan leader wants 'Gates of Hell' fire put out

No golden age

However, preindustrial life was no halcyon era when our ancestors went about their day well rested and rejuvenated, untroubled by insomnia or other sleep problems, effortlessly in sync with the cycle of night and day, weather patterns and seasons, according to Sasha Handley, a professor of history at The University of Manchester in the United Kingdom.

She studies how families optimised their sleep in Britain, Ireland and England's American colonies between 1500 and 1750.

"Every discussion of sleep history seemed to center around the sort of watershed moment of industrialisation, the coming of electricity ruining everybody's sleep lives. The corollary of that is that anything preindustrial was imagined as this golden age of sleep," she said.

Professor Handley said her research suggested, just like today, sleep was linked to physical and mental health and was a topic that people worried about and obsessed over.

Doctor's manuals from the time are full of advice on how many hours to sleep and in what kind of posture, she said.

The reference guides also list hundreds of sleep recipes to aid a good night's sleep, she said.

These include the bizarre - cutting a pigeon in half and sticking each half to each side of your head and the more familiar - bathing in chamomile-infused water and using lavender.

People also burned specific types of wood in their bed chambers that were thought to aid sleep.

"For our period, sleep is very strongly linked to digestion, emotion, stomach, and therefore to people's diets," Professor Handley said.

Doctors advised sleepers to rest first on the right side of their body before turning to the left side during the second half of the night.

Resting on the right, perhaps during the first sleep, was thought to allow food to reach the pit of the stomach, where it was digested. Turning to the left, cooler side, released vapours and spread the heat evenly through the body.

It's thought this habit could be the origin of the phrase about getting out of bed on the wrong side.

Not all scholars believe that sleeping in two shifts, while perhaps common in some communities, was once a universal habit.

Far from it, said Brigitte Steger, a senior lecturer in Japanese studies at the University of Cambridge in the UK, who didn't uncover any references to segmented sleep in her work on sleep habits in Japan.

"There is no such thing as natural sleep. Sleep has always been cultural, social and ideological," Ms Steger, who is working on a series of six books about the cultural history of sleep, said.

"There is not such a clear-cut difference between premodern (or pre-industrial) and modern sleep habits," she said via email.

"Sleep habits throughout pre-industrial times and throughout the world have always changed - and, of course, there has always been social diversity, and sleep habits have been very different at court than for peasants, for instance."

Similarly, Gerrit Verhoeven, an assistant professor in cultural heritage and history at the University of Antwerp in Belgium, said his study of criminal court records from 18th century Antwerp suggested that sleep habits weren't so different to our own today.

Seven hours of sleep was the norm and there was no mention of first or second sleep.

"As a historian I'm concerned that arguments about alleged sleeping patterns in the past - prolonged, by-phasic and with napping during the day - are sometimes presented as a possible remedy for our modern sleeping disorders," Professor Verhoeven said.

"Before drawing such conclusions, we have to do much more research about these early modern sleeping patterns."

READ MORE: Saudi princess freed after nearly three years in jail

Rethinking insomnia

Russell Foster, a professor of circadian neuroscience at the University of Oxford, said Professor Ekirch's findings on biphasic sleep, while not without controversy, had informed his work as a sleep scientist.

Experiments in sleep labs had shown that when humans are given the opportunity to sleep longer, he said, their sleep can become biphasic or even polyphasic, replicating what Professor Ekirch found in historical records.

However, Professor Foster, who is also the director of the Sir Jules Thorn Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Institute at Oxford, doubted that it was a sleep pattern that would happen for everybody.

Nobody should impose a regime of segmented sleep on themselves, particularly if it resulted in a reduction of total sleep time, he added.

What was clear, Professor Foster said, was that interrupted sleep was perceived as less of a problem in the past and that modern expectations about what constitutes a good night's sleep - sleeping through the night for eight hours - weren't always helpful.

He said a key point was waking at night need not mean the end of sleep. One example he cited was more people waking up at night during lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic.

"They'll get terribly anxious and worried about waking up in the middle of night, because that's not what they normally experience," Professor Foster, who is also the author of "Life Time: The New Science of the Body Clock, and How It Can Revolutionize Your Sleep and Health," which will be published in May 2022, said.

More likely, what had happened was that people's sleep episode - how much time they have available for sleep - had expanded and wasn't constricted by an alarm clock going off.

"It's a throwback to a time when we genuinely got more sleep," he said.

If we wake up at night, sleep is likely to return, if sleep is not sacrificed to social media or other behaviour that makes you more alert or activates a stress response, Professor Foster's research has suggested. Like most sleep experts, he recommended getting out of bed if you're getting frustrated by the failure to fall back to sleep and engaging in a relaxing activity while keeping the lights low.

"Individual sleep across humans is so variable. One size doesn't fit all. You shouldn't worry about the sort of sleep that you get," he said.