Charlotte Carrabs remembers being 19 years old and sitting in the office of her plastic surgeon as he talked her through the procedure for breast augmentation.

He gave her a bizarre demonstration of just how indestructible the textured implants she was having inserted into her body were.

"He said, 'They're really strong, check this out,' and he grabbed an implant and chucked it in the door and then slammed it," the now 26-year-old recalled.

"He said the pressure of the door wouldn't even break the implant.

"I was a bit shocked."

READ MORE: What we know about the BA.2 'stealth' Omicron variant

Aside from her surgeon mentioning she may need to replace her implants after a decade or so, Ms Carrabs cannot recollect any discussion during the pre-surgery consult about potential health risks.

"I don't think we ever touched on any associated risks. There was no talk about my body possibly rejecting the implants or that I could have issues later on," she said.

READ MORE: Defiant Russian news worker interrupts state TV

Ms Carrabs would go on to suffer a myriad of debilitating symptoms over the next seven years, none of which she was warned about.

Many of the symptoms Ms Carrabs endured are associated with what has come to be known as Breast Implant Illness (BII).

BII is not a medically-recognised condition but there are growing calls for more research and investigations into its causes and risk factors.

It started with a rash

The first sign that something was wrong came seven months after breast augmentation surgery, although she didn't connect it to her implants at first.

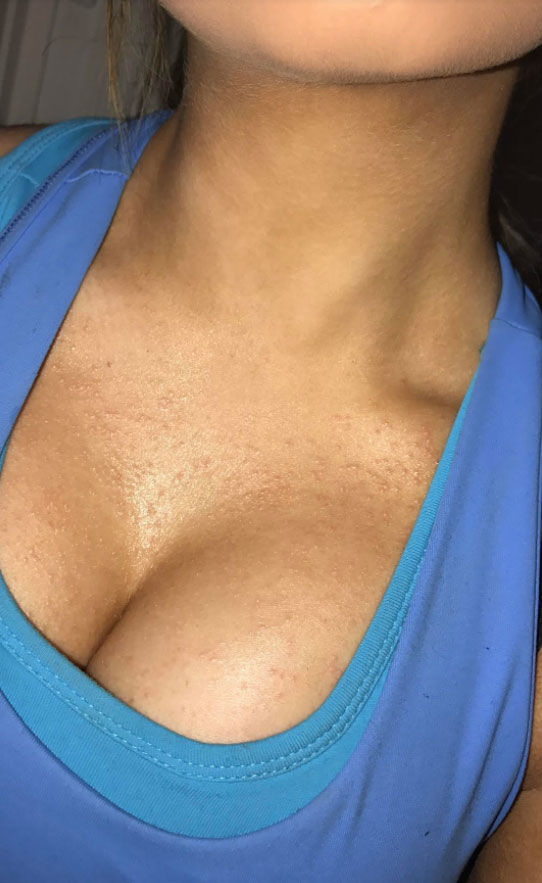

"I got this viral rash that started on my chest, and it kind of spread up to my neck to my ears," Ms Carrabs said.

Initially, Ms Carrabs thought it was an allergic reaction to something she had eaten, but the rash kept on coming back.

Then there were other strange symptoms that developed over the next few years, like chronic fatigue, brain fog and issues with her gut.

Ms Carrabs also started getting sharp pains in her chest.

Eventually, with the help of breast implant illness groups online, and a GP who had treated other women with similar experiences, Ms Carrabs was able to pinpoint her breast implants as the cause of her ill health.

"It's an awful feeling when you kind of connect the dots and go, oh my gosh, I need to get this foreign object out of my body," she said.

"It's quite frightening because it just felt like a ticking time bomb."

Ms Carrabs had her breast implants removed six weeks ago.

The effect of the surgery was dramatic, she said.

"Immediately after the surgery. I just felt like I could breathe again. I could take a deep breath in and nothing was restricting my breathing," she said.

"I'm no longer experiencing that sharp stabbing pain and my chronic fatigue has lifted.

"My husband said to me, 'you are like a different person, you're just so much brighter, so much more energetic.'"

Breast implant removals soar

According to the Australian Breast Device Registry (ABDR), an estimated 20,000 women undergo breast augmentation surgery every year in Australia - for cosmetic reasons or reconstruction after cancer.

Despite the high numbers, Ms Carrabs is one of a growing number of women in Australia who are choosing to have their breast implants removed.

Breast implant removals, or explants, have increased more than sixfold over the past decade, Medicare data provided to 9news.com.au by the Federal Health Department shows.

Last year, 4903 women had breast implants removed, up from 1234 in 2016 and 762 in 2011.

Sydney-based plastic and reconstructive surgeon Anand Deva believes the figures show the start of a trend towards women becoming more conscious about the health risks of breast implants.

"Breast augmentation still remains the number one cosmetic procedure performed around the world, but - for the first time ever - we've seen a drop in that and a comparative rise in the number of explants," Professor Deva said.

Increasing evidence of breast implant-related cancer had led to a number of textured types of implants being removed from the Australian market in 2019, he said.

Past scandals over silicone-based implants as well as regular media reports about under–qualified "cosmetic surgeons" had also impacted the industry, he added.

Meanwhile, the power of social media had been a "gamechanger", Professor Deva said, allowing women to communicate and share experiences for the first time.

Australian study examines BII

Prof. Deva is now leading Australia's first study into the symptoms of women who believe they have breast implant illness.

The Sydney Macquarie University study is currently tracking the symptoms of 200 women before and after they have the operation.

Prof. Deva said he hoped to expand the study to include 1000 women over the next few years, as the evidence-led research looks at why some women become so sick after implant surgery.

Preliminary findings from the study, based on 45 women six months after surgery - found in 70 to 80 percent of them many symptoms lessen or disappear entirely after their implants were removed, Prof. Deva said.

The findings are in line with published results from a similar study of women with breast implant illness conducted in the US, he said.

As well as monitoring symptoms, researchers will examine and run tests on the implants removed from the women in a bid to find possible causes for their symptoms.

Professor Anand said tests on the first 45 women in the study showed 70 percent of them had bacteria on their implants, but whether it played a role in their illness was still unclear.

While the most common complication of breast implants was a hardening of the breast tissue and associated pain, the symptoms of breast implant illness were as varied as they were debilitating, Professor Deva said.

Possible signs include brain fog, fatigue, anxiety and depression, joint pains, loss of hair and changes to skin rashes, he said.

In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration ordered manufacturers to inform women of the "serious and life-threatening risks" of breast implants, a so-called "black box" warning similar to what is found on cigarette packets.

In Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administrator is yet to make such a move, but is considering guidelines for informed consent.

The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) is also currently conducting an inquiry into the cosmetic surgery industry.

Professor Deva said reform was desperately needed to make sure women were aware of the risks of implants.

"Ultimately, it's about making sure every woman thinking about an implant is fully informed and educated on the risks.

"For a lot of the women I see, this was never discussed. And so, when they find themselves really, really sick and struggling for answers, they feel a little bit betrayed. Why didn't the surgeon inform me this could be the case?"

Shelly's hands turn blue-black

Mother-of-three Shelly Rafferty is one of the 200 women participating in the Macquarie University study.

Ms Rafferty said she went from being a healthy, active 34-year-old to someone with multiple chronic health complications after getting her breast implants inserted 10 years ago.

Over a period of almost a decade, she endured two strokes, spontaneous tears in both carotid arteries in her neck, tears in her oesophagus and chronic eye, joint, chest, back and hip pain.

Her hands turned a blue-black colour.

Every time she boarded a plane, Ms Rafferty had to travel with an oxygen concentrator because of low oxygen saturation and constant shortness of breath.

In March 2020, Ms Rafferty underwent surgery to remove her breast implants.

The surgery was transformative.

"I feel like I have my life back," she said.

"I can take my kids to school and dance classes, walk my dog, go out for dinner and not go to bed at 7pm – things most people take for granted. Money can't buy what I've got back."

Professor Deva is seeking more participants for Macquarie University's study. Click here for more information.