How do you tell a story when the final chapter is public knowledge?

You start at the end.

Fire of Love, Sara Dosa's moving documentary about husband-and-wife volcanologists Maurice and Katia Krafft, begins on June 2, 1991, at Mount Unzen in Japan.

READ MORE: Rare drone video shows moment orcas kill great white shark and eat its liver

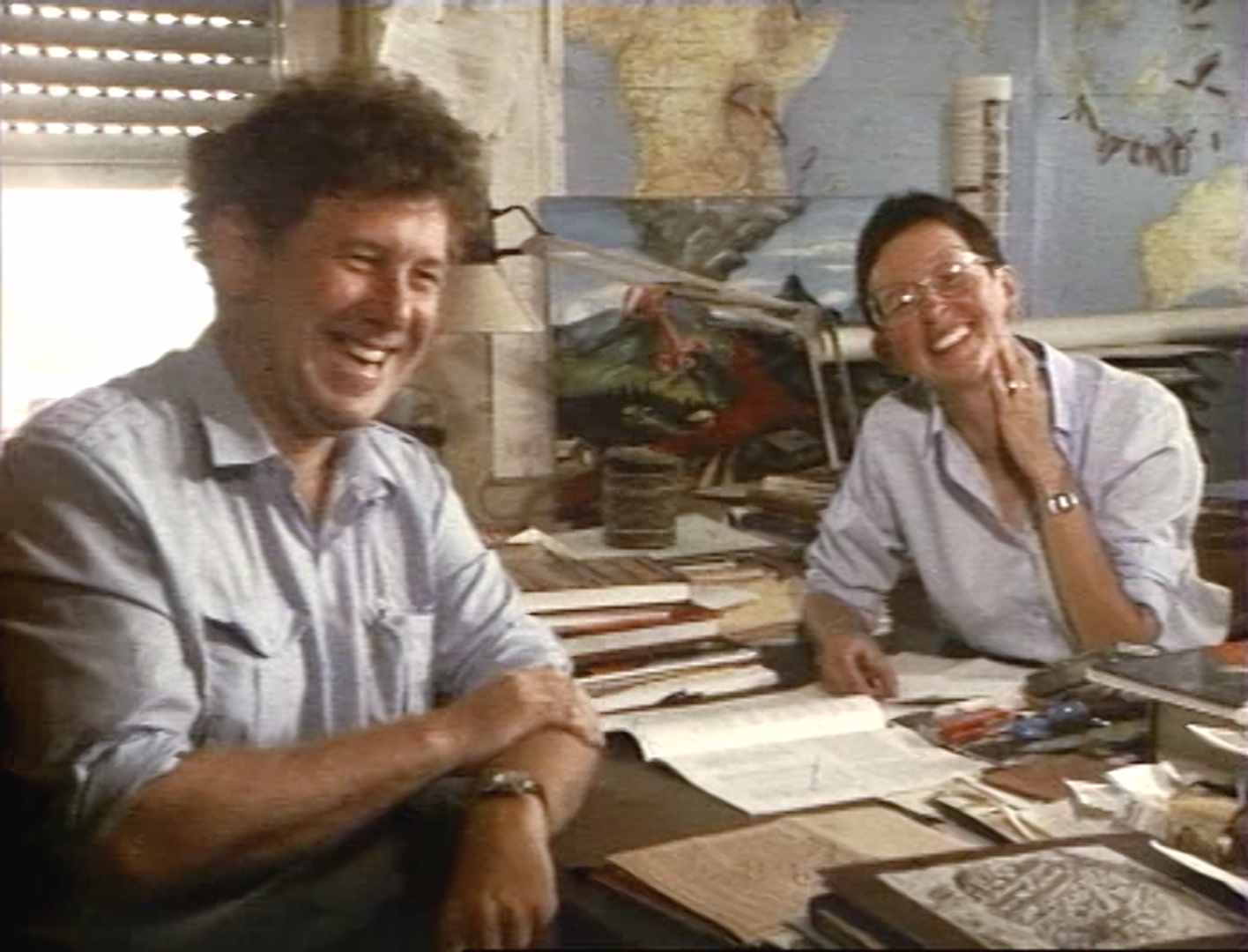

The Kraffts, rockstar scientists in their field, are seen in a buoyant mood in archival footage.

But narrator Miranda July quickly punctures that.

"Tomorrow will be their last day," we're told via her voice over.

Unzen would erupt on June 3, killing the Kraffts along with 41 others in a pyroclastic flow.

It's an ending so definitive, there was no choice but to start there.

"We really didn't want the audience to be focused on how Katia and Maurice might die... instead, we hoped people would focus on how they live," the director told Sara Sidner in an interview for CNN's Amanpour.

"This is a collage film that's told through... their footage, their photographs, their writings, and we wanted the audience to know first and foremost that what they are watching is (what the Kraffts) left behind when they passed. So, we had to acknowledge their death."

The film comprises excerpts from around 200 hours of footage taken by the couple for their own research and documentaries, along with media interviews and extracts from their books.

READ MORE: Russian battlefield casualties in Ukraine 'more than 75,000'

Fire of Love has drawn near universal praise in reviews, first at Sundance in January and leading up to the film's release in the US and the UK this summer.

Armed with a 16mm video camera, the French scientists captured the intimate lives of volcanoes from the Democratic Republic of Congo to Colombia to the United States.

In vivid hues, lava burbles and races, rocks fly, these agitated mounds full of sound and fury, wrestling with their creative and destructive potential.

Working with editors Erin Casper and Jocelyne Chaput, Dosa harnesses the volcano footage's anthropomorphic qualities to illustrate the Krafft's relationship with each other and their subjects.

"We like to think of the film as a love triangle between Maurice, Katia and volcanoes," she explained.

Katia and Maurice met in the 1960s through their common interest.

Their personalities contrasted, Maurice gregarious and devil-may-care, Katia quieter and observant; differences that carried over into their fieldwork.

In one scene we see Katia unamused as her husband rows out into a lake of sulphuric acid (and then faces over three hours of paddling into a headwind to get back to shore).

"It will kill me one day," Maurice says of his job.

Katia was often trying to ensure it didn't - even if she was hardly risk-averse herself.

In one of the documentary's many eyebrow-raising scenes, she stands, calm and collected, on the edge of a crater while measuring a temperature of 1200 degrees Celsius.

Asked to describe their relationship by an interviewer, Maurice quips, "It's volcanic - we erupt often!"

"They had a conflict there," Dosa said.

"They were usually able to reconcile though, because they knew that it was so important to be in sync with each other, to support each other, if they were going to pursue their ultimate love, which was being close to erupting volcanoes."

The Kraffts knew how to leverage their daring pursuits to gain fame and financing to continue their research; their image-making was not a selfless exercise.

But it's to Dosa's benefit and ours that the Kraffts were, in their words, so "fascinated, like a magnet, getting closer and closer" to danger.

"It's really thanks to their love and their boldness, to get so close to capture these images, that we have them now in our film," Dosa said.

And though "they died truly doing what they loved," their legacy has prevented many more deaths.

The Krafft's footage of a pyroclastic flow in 1986, for example, was used in an educational video to help governments understand their dangers, the director explained, and a week after the couple's death its lessons were put into practice when Mount Pinatubo erupted in the Philippines.

"The video helped to save many lives," Dosa said.

"It's quite tragic, but poetic."