For eight torturous years, a Sydney mother grappled with a "slow-building" bladder infection; one that would leave her rushing to go to the bathroom "every 45 minutes to an hour", even through the night.

Laura Cunningham, from Camden in the city's south-west, first noticed the symptoms around 2010, but in 2017 her condition would deteriorate and result in repeated visits to her GP - and the emergency department.

Yet every urine test would come back negative.

READ MORE: Common UTIs risk turning into killer infections

Have you, or someone you know, struggled with UTIs? Contact Raffaella on rciccarelli@nine.com.au.

The mother-of-one didn't know she had a chronic urinary tract infection (UTI).

To get that diagnosis, she would need to undertake a journey of more than 17,500 kilometres and live through some of her "darkest days".

A UTI is a common infection one in two women will experience in their lifetime, but even Cunningham said she mistook her symptoms initially.

Chronic UTI Australia, a national advocacy group, explains chronic infections are different.

They arise when "intracellular bacteria burrow into the bladder and/or urethral lining (uroepithelium) where they safely hide away from further immune or antibiotic attack".

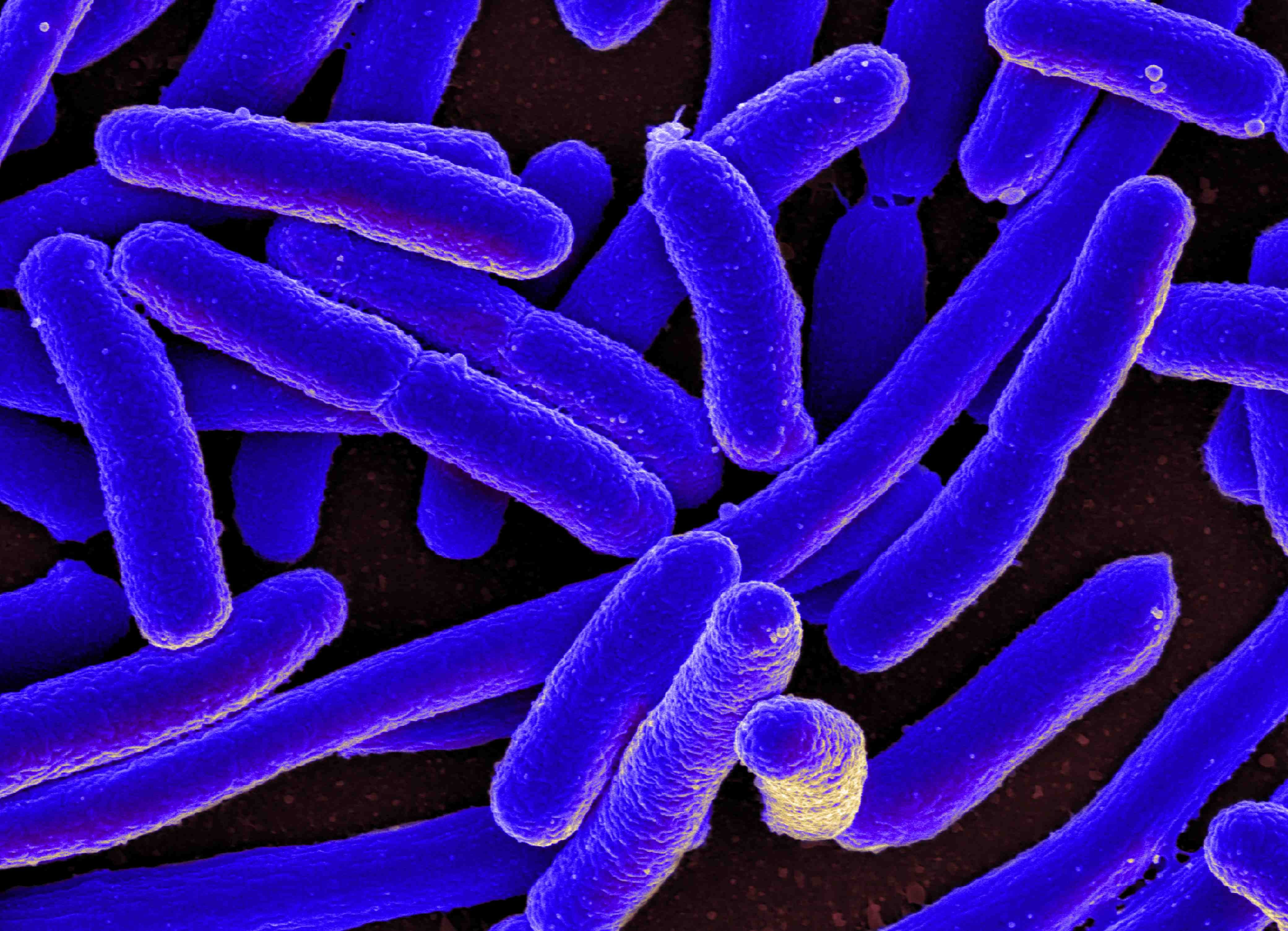

Research shows certain bacteria, like E. coli, can lay dormant in the lining, and flare up when conditions are optimal, which creates UTI symptoms.

READ MORE: Brisbane woman in pain for years as 'common' infection went undiagnosed

"I'd say I first really started to notice the frequency around 2010. It built ever so slowly, I kind of just adjusted," Cunningham told 9news.com.au.

"I didn't think it was a UTI initially because it was more mild.

"There was no burning, just that frequency.

"I suffered for many years without even knowing it."

Cunningham realised something was not quite right when the frequency started to impact her sleep.

"It went on for maybe eight years at least of slowly building, more frequency through the night, to the point I was going to the bathroom every 45 minutes to an hour, through the daytime," she said.

"I remember bringing it up with my doctor and they just said, 'Wait till you have a baby, it will just get worse.'"

Her GPs would treat the symptoms with a short course of antibiotics - even though her UTI tests "would always come back negative".

"I'd take the antibiotics they'd give me and within hours I would be fine," Cunningham said.

'I was slowly dying'

But then in 2017, something changed.

At the age of 35, Cunningham's symptoms flared up - and this time she had urgency, a busting feeling of needing to urinate.

She went to her doctor, as always, and was prescribed antibiotics, as always, but this time they didn't take.

"After a couple (of) days, while I was still taking the course, the symptoms came back," she said.

"That was really frightening, I thought, 'Now what?'

"I went back to the doctor and he called (a) special commission in Canberra to get a different antibiotic, which initially worked and then again two days later it came back again.

"It was just scary, isolating."

READ MORE: Scientists have found new 'zombie viruses', should we be worried?

At this point, Cunningham was going to the bathroom to urinate so often she wasn't sleeping.

"I can't say it got worse because there was no worse. It was just a constant state of busting," she said.

"There wasn't a period of the day I wasn't completely needing to go."

After four days "without a wink of sleep", she turned to hospitals for help but that help proved elusive.

"I thought this would be the end of me. I was slowly dying," she said.

"I remember going to three different hospitals as I knew it was an infection but no one would believe me.

"The test would come back negative and they'd tell me I'm clear of a UTI and they'd send me on my way."

READ MORE: How skipping just one night of sleep could age your brain

Increasingly desperate, Cunningham found herself a urologist to investigate.

"He put me on an antibiotic drip overnight a few times and I started to feel a tiny bit better," she said.

"But after one night he put me on overactive bladder medication and left me on that."

After a cystoscopy, a procedure which sees a long tube with a camera attached inserted inside the urethra and bladder, Cunningham was diagnosed with interstitial cystitis - a chronic and painful bladder condition often mistaken for a UTI.

But Cunningham wasn't convinced with the diagnosis, as she had found short-lived relief through antibiotics.

"He told me I can stay on the medicines for overactive bladder 'forever'," she said.

"They saved my life as far as any specialist could help in Australia, they treated the frequency a little bit, but they weren't treating the infection.

"I kept telling him, 'I know it's an infection', and would ask him, 'Why else would the antibiotics have worked initially?' but he wouldn't listen."

That's when Cunningham started Googling.

The article that changed Laura's life

After six months of plugging in the same search term - "UTI with negative test results" - she got a hit.

"I Googled and I Googled for six months and one day an old newspaper article from England popped up," she said.

That article introduced Cunningham to Professor James Malone-Lee, who had begun researching the possibility of chronic UTI in London.

"Straight away I said, 'I know this is what I've got'," she said, explaining she emailed the professor and heard back after a month.

"I booked a flight straight away and I went out there."

READ MORE: Louisville bank employee livestreamed attack that killed four

In early 2018, Cunningham flew from Sydney to London via Dubai on a Qantas A380.

Her "sweet" husband used all his available points to secure a seat; the only one happened to be in first class.

Her son was just three-years-old at the time.

He and Cunningham's husband would later join her on the two-week trip.

Upon arrival, Cunningham was amazed to learn Malone-Lee's clinic, Harley Street, had a different approach to diagnosing UTIs compared to the dip tests and midstream urinary cultures used worldwide.

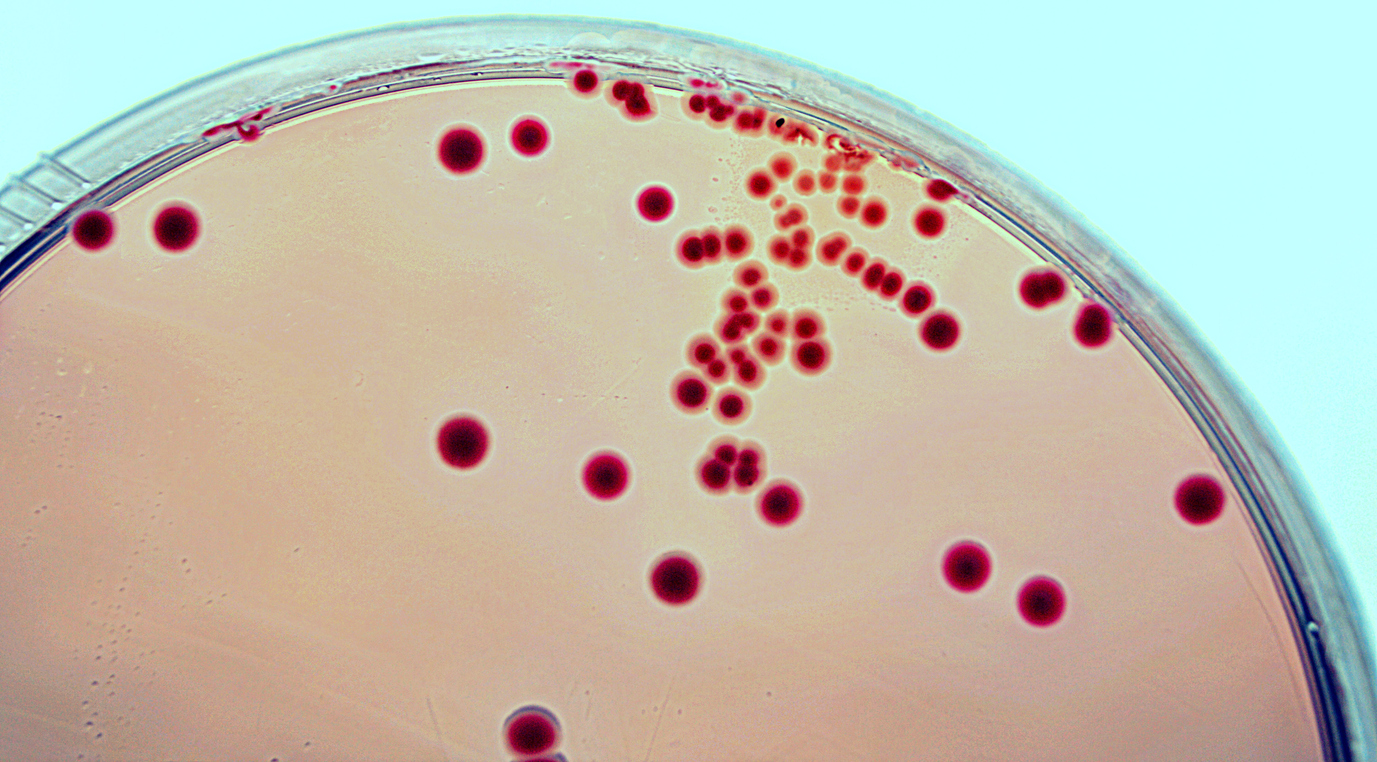

Research shows urine dipstick tests, the preliminary tool GPs use to test for indicators of a UTI, can miss up to 70 per cent of genuine infections.

From there, GPs will often send urine off to a laboratory - as part of a midstream urinary culture - to see if bacteria can be "grown" from the sample.

Those tests are believed to miss between 50 and 80 per cent of infections.

Cunningham said the professor didn't need to look for bacteria to diagnose her chronic UTI.

Instead, he looked for epithelial cells, which cover all body surfaces internally and externally.

A large number in urine could signify an infection.

"The professor looked at my fresh urine straight under the microscope," she said.

"He was looking at the epithelial cells from the shedding and the white pus cells, which are signs of infection.

"After doing a count, he then gave the treatment plan of high dose, long-term antibiotics."

On arriving back in Australia after two appointments, Cunningham said she was "lucky" that her GP was more than happy to follow the prescription plan.

Cunningham was on a high-dose course of antibiotics for two years.

She's now stopped taking it and is no longer on overactive bladder medication.

Malone-Lee has since died but Cunningham said he changed her life.

"Life is amazing compared to then," she said.

"They were the darkest days of my life, especially those four days without a wink of sleep.

"It was such a relief I finally had an answer.

"I knew it was an infection, I kept telling every single specialist I saw - and there were a lot - and no one believed me.

"The professor finally did. I'm so happy to have my life back and just to be here with my boy."

Chronic UTI Australia said "there are currently no practitioners in Australia that specialise in diagnosing and treating chronic UTI that we know of" and the condition is largely unrecognised.

Cunningham believes one of the "big failures" in the medical system is the over-reliance on the dip test and midstream urinary cultures as diagnostic tools for UTIs.

"I would love it if urologists had more hands-on experience, look at fresh urine under the microscope," she said.

"I think that should be standard, to do it the way (the) professor did.

"It's not tested two hours later, it is looked at straight away."

Sign up here to receive our daily newsletters and breaking news alerts, sent straight to your inbox.