When someone first told conservationist Jess Abrahams they were worried about the koala becoming an endangered species twenty years ago, he admits he found the idea absurd.

"I literally laughed at them. I said, 'What are you talking about? Koalas are everywhere'," he said.

"As a kid they were there on my grandfather's farm, they were all along the Yarra and throughout Eastern Australia.

"And wow, within 10 years, koalas were vulnerable and last year they were endangered."

We've seen it throughout history - catastrophic events colliding to wipe out a species that appeared to have been thriving.

Perhaps one of the most famous examples is that of the passenger pigeon in the US.

The passenger pigeon was once the most abundant bird in North America, numbering in the billions and migrating in enormous flocks.

But deforestation and rampant hunting throughout the 19th century saw their numbers steadily decline, to the point where the last passenger pigeon was shot in the wild in 1900. The species has now been extinct for more than a century.

Droughts, floods, bushfires and habitat destruction has led to Australia being in the midst of an extinction crisis, Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) nature campaigner Peta Bulling said.

"Australia is leading the way with one of the worst extinction rates on earth. Our threatened species list is approaching 2000 with new plants and animals being added regularly," she said.

With this in mind, here are some of our iconic Aussie animals that appear to be disappearing before our eyes, including a few that may come as a surprise.

The platypus

With cash no longer king, it's becoming rarer to catch a glimpse of a 20c coin featuring the platypus in our wallets these days.

But that's nothing compared to the chances of spotting the real thing - a platypus in the wild - which has plunged to almost zero for anyone living in Sydney.

While the iconic monotreme once happily ducked and dived in the NSW capital's riverbanks, the platypus is believed to have now almost completely vanished from the Sydney Basin.

"Reliable sightings of a platypus haven't been recorded in the Sydney Basin anytime in the past few years," Abrahams, who leads the ACF's Platy-Project, said.

"The most reliable place you can still see them is at the foot of the Blue Mountains in the Hawkesbury river."

One notable exception appeared to be the semi-rural suburb of Dural, in Sydney's far north-west, where one local had logged several sightings over the past two years, Abrahams said.

Likewise in Victoria, the platypus would have once been a common sight in the Yarra River, but the quirky creature can now only be seen in select outer suburbs, such as Eltham in the north east.

Brisbanites too, would need to travel some 10-15 kilometres out of the city to have any chance of seeing a platypus in the wild, Abrahams said.

In fact, the only capital city the platypus was yet to abandon was Hobart, he added.

Hobart GP Jessica Kneebone knows the magic of spotting a platypus in the wild.

Last month, Kneebone was on a nature walk led by Abrahams, along the rivulet around 4km south of the city, when the group came across a platypus.

"It was ducking around in a shallow pool and diving and kind of hiding in the bushes," she said.

"We all went quiet and there was definitely a sense of excitement and awe."

Kneebone, who lives near the rivulet, said she was lucky enough to have seen many platypus in their natural habitat, and some in surprisingly urban settings.

"I've seen them at South Hobart Primary School, which is only about 1km from the city and with bike paths on both sides of the rivulet," she said.

The platypus has been listed as endangered in South Australia and vulnerable in Victoria.

The ACF believes the platypus should be labelled as threatened nationally.

Abrahams said it was hard to say how many platypus were left in Australia, but recent research found their habitat had shrunk by at least 22 percent, or about 200,000 km2 - an area almost three times the size of Tasmania - over the past 30 years.

So what can we do to help?

The Platy-Project, which partners with University of New South Wales, has created a map of all historical sightings of the platypus. Abrahams said anyone could go on and log new sightings of the platypus to help researchers glean information about their numbers and location.

Blue-tongue lizards

It's not just the platypus that has been making a quiet retreat.

Blue-tongue lizards were once the lords of the Aussie backyard, seen lumbering around and scaring off predators.

But experts believe the iconic blue tongue lizard could be becoming far less common than we realise.

Australian Museum herpetologist Dane Trembath said eastern blue-tongue lizards – found in south-east Australia - appeared to be hardy creatures that could survive even in the deepest of suburbia.

"Blue tongues are quite amazing animals in that they still live within the inner city of Sydney," Trembath said.

"I had one sighting reported to me the other day at Balmain and another one in Leichhardt."

However, the city's urban sprawl had come with habitat destruction as well as the increased danger of cars and predators, such as cats and dogs, Trembath said.

"Anecdotally, I think people are saying they are seeing less blue tongues around," he said.

While there had been little research done on eastern blue-tongue lizard numbers, scientists have shown a definitive decline in the subspecies of blue tongue - found in northern Australia - due to poisonings from cane toads, Trembath said.

Meanwhile, the endangered pygmy bluetongue, the smallest subspecies, is found in only 30 locations, all across the Adelaide plains, where it lives in the former burrows of trapdoor spiders.

Christmas beetles

Christmas beetles were once synonymous with an Australian summer, arriving in great hordes every November.

"In the 1920s, they were reported to drown in huge numbers in Sydney Harbour, with tree branches bending into the water under the sheer weight of the massed beetles," Australian Museum entomologist Chris Reid recalls.

However, Reid and other experts have noted an "anecdotal yet compelling" decline in the seasonal scarab.

"People remember them being around in huge numbers around Christmas," Associate Professor Tanya Latty, an entomologist at the School of Life and Environmental Sciences said last year.

"But that just doesn't seem to happen anymore, particularly on the east coast of Australia.

So where have all the Christmas beetles gone?

Climate change and a loss of natural habitat are two logical explanations for the bugs' decline, but more research is needed to be sure.

Come summer if you see a suspected Christmas beetle, take a photo and upload it to iNaturalist.

Bogong moths

Once so numerous that they'd seemingly black out the moon, the bogong moth suffered a population crash of up to 99 percent five years ago and has not made a full recovery since.

Linda Broome, who works for the New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage and has been monitoring the moth for more than 30 years, said the moth had seen plentiful years in the past.

In 2012, great swarms of bogong moths converged on Canberra's Parliament House, setting off alarms and taking over the Senate chamber.

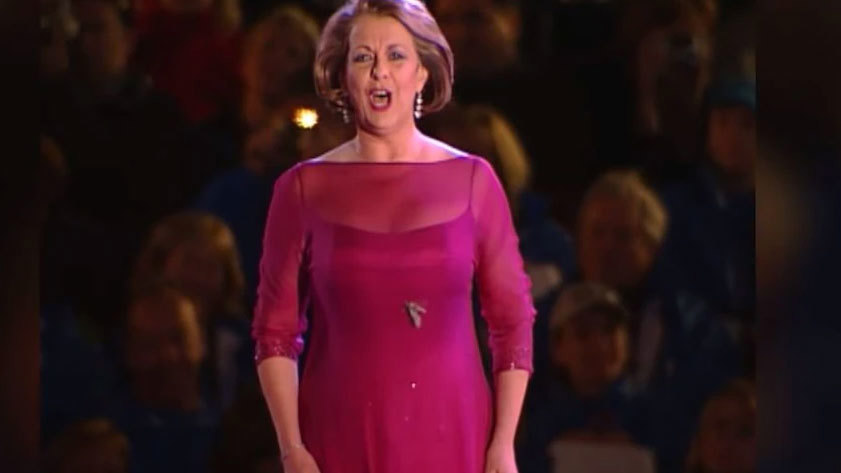

Dazzled by the lights at the Sydney Olympics closing ceremony in 2020, bogong moths descended to cause panic, with one even landing on the torso of legendary soprano Yvonne Kenny as she sang the Olympic Hymn.

But by then, Australia's ongoing drought in the east had already made a huge dent on bogong moth numbers.

Broome records numbers of bogong moths in light traps at Mount Kosciusko as they complete their annual migration south to the Alps.

"There was certainly a decline in the numbers I was getting in 2017, but the lowest year was 2021," Broome said.

Extensive flooding in the moth's breeding grounds was likely to have delayed the moth's recovery even after the drought broke, Broome said.

"We thought there's billions of bogong moths, nothing could ever happen to them, but it's a bit like the passenger pigeon, isn't it?" she said.

"Suddenly something happens and we realise they're actually quite vulnerable."

However, numbers of the moth - which provide an important food source for animals like the critically endangered mountain pygmy-possum - appear to have recovered somewhat in the last year, rising to about 50 percent of its pre-drought population, she added.

Sign up here to receive our daily newsletters and breaking news alerts, sent straight to your inbox.