It's often said power and corruption go hand in hand and no-one knows the truth of that better than Kate McClymont.

Over almost five decades, The Sydney Morning Herald's chief investigative reporter has held the powerful to account, probing the depths of Australia's underbelly of crime, corruption and fraud.

Her fearless reporting has led to death threats from underworld mobsters and seen her head to the courtroom perhaps more than any other Australian journalist.

McClymont, who was last night honoured with a special Walkley Award for her Outstanding Contribution to Journalism, has broken some of the country's biggest scandals.

https://omny.fm/shows/liar-liar/melissa-caddick-fraudsters-death-to-remain-a-myste/embed?style=coverMost recently, she has led investigations into serial financial fraudster Melissa Caddick, high-profile neurosurgeon Charlie Teo and High Court judge Dyson Heydon.

McClymont, alongside 60 Minutes producer Thea Dikeos, was also a finalist in the Walkley's investigative journalism category for her reporting on Teo this year.

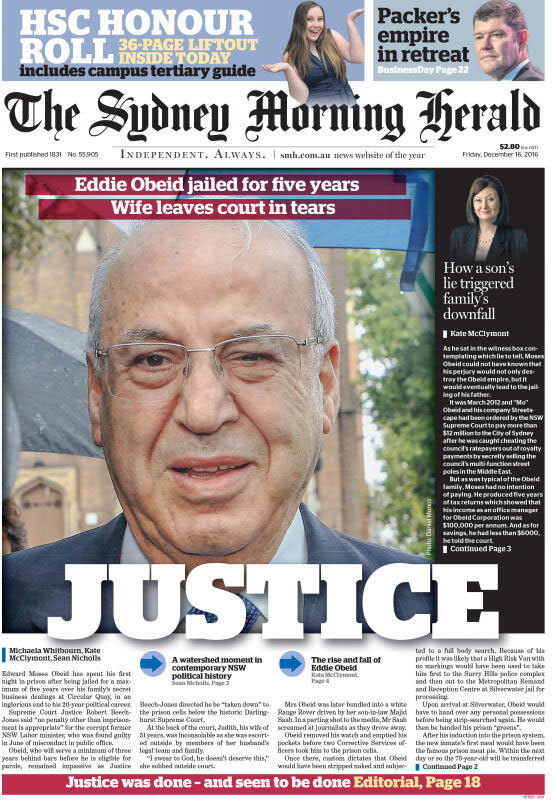

However, McClymont is perhaps best known for breaking the Canterbury-Bankstown Bulldogs' NRL salary cap scandal and her investigation into former Labor powerbroker Eddie Obeid - which spanned 17 years and led to Obeid being jailed not once but twice.

Somewhat surprisingly, it was in the style section of The Sydney Morning Herald that the nine-time Walkley Award winner got her start as a journalist - back in 1985.

"I think I got my first complaint then," McClymont told 9news.com.au.

"I did something on the 10 best beds of Sydney, and one of the big advertisers complained that I didn't feature one of their beds."

"I'm 'independent always'," McClymont joked, with a tongue-in-cheek reference to the Herald's tagline.

From the style section, McClymont was moved to cover the society column at the Eastern Herald, where she admits she "sort of went a little bit rogue".

Bored with covering the same people at the same events, McClymont saw her chance to have a little fun when she attended a Rosebay wedding in Sydney's eastern suburbs.

The wife of George Freeman, one of the underworld figures of the day, was in the bridal party, while the couple's son - who later spent time in jail - was a young and innocent ringbearer.

In her write-up of the event, McClymont observed the bridal party was wearing sequins "which was the closest fashion accessory to armour plating that you could get away with".

"That's when I got my first death threat for making fun of the bridal party," McClymont said.

"George didn't think it was very fun.

"My flatmates were getting calls from someone saying, 'George is not happy'. And they were saying, 'Does anyone know who George is?'"

Despite the seriousness of the many death threats McClymont has received during her career - she has had to relocate her family twice because of credible fears - McClymont said they did sometimes lead to levity.

While covering the contract killing of Sydney businessman Michael McGurk in 2009, a threatening note was delivered to McClymont's house.

"The note said something about 'watch out for a .303' and I said to my husband, 'Do you think that actually means a gun, or just our address', which was 303. They didn't actually specify."

McClymont said she refused to be cowed by the death threats, which were all done with the aim of getting her to stop writing.

"If somebody really wanted to kill you, they actually would. There is nothing that you can do, so you might as well not worry about it. And the thing is, you don't know where it's going to come from," she said.

"One of my police contacts said to me, years ago, it's the people that don't threaten you are the ones that you have to worry about."

Unlike the death threats, the criminals and fraudsters McClymont has investigated over the years have been a bit more predictable.

Many of these corrupt figures had personality traits in common, she said.

"A lot of the people I write about have narcissistic personality disorders; people like Melissa Caddick, the fraudster.

"The reason they can do the crime in the first place is they never lose one minute's sleep doing something wrong.

"And they're also often the same people that think that they can sue you, because they just can."

The regular rhythms of the underworld had also made themselves known to McClymont over the years, with many of the same notorious figures reappearing with their fingers in different pies.

"I am constantly shocked by the connections in the Sydney underworld between accountants, lawyers, the footsoldier," she said.

"There will be people I write about who turn up 10 years later in somebody else's story.

"I think that is also the benefit of being around for a long time - you recognise the names."

In McClymont's offices at Nine, there are bulging records that help jog her memory and detangle the interweaving web of Sydney's criminal underbelly.

"I have got files in alphabetical order of almost every person I've ever written about. I need some more room," she said.

"It's funny, you get those files out, and just go, 'Oh yes, I'd forgotten about that.''

Recently, McClymont's investigations have challenged the perceptions of some Australia's most respected figures.

Her coverage of Charlie Teo led to sanctions against the controversial neurosurgeon.

A joint investigation with Tracey Spicer in 2017 exposed serious misconduct by television star Don Burke.

McClymont said taking on these stories was not a decision she made lightly.

"You know there's going to be blowback (but) you do these things for a reason," she said.

"You do these things because you are the voice of people who don't have a voice, and it's important that we are not cowed by somebody's reputation, or hero status.

"You just have to do the story as it needs to be told."

McClymont said it was becoming harder for journalists to tell these sorts of stories and the current defamation laws in Australia were "the biggest drag on investigative journalism".

"In the US, their public figures basically can't sue. If they do sue, they have to prove that you were wrong, that you lied, and you did so with malice," she said.

In Australia, the onus of proof was reversed, McClymont said.

"You have to prove that everything you said in a story was correct."

One recent bright spot, however, was the Herald's win against former Australian soldier Ben Roberts-Smith, who sued the newspaper for defamation after the masthead exposed war crimes he committed in Afghanistan.

The case is currently being appealed.

"The Ben Roberts-Smith case has been a major boost to investigative journalism," McClymont said.

"It was really a major victory for press freedom."

When asked about her Walkley for Outstanding Contribution to Journalism last night, McClymont said she was incredibly honoured but somewhat worried it might give some people the false impression she was heading for retirement.

McClymont said she definitely had no such plans.

"I am going to drop dead at my desk with my head banging onto my computer," she said.

Seven other female journalists were also awarded with the same honour last night - Geraldine Doogue, Karla Grant, Joanne McCarthy, Colleen Ryan, Marian Wilkinson, Pamela Williams and Caroline Wilson.

This year, the Walkley Foundation directors decided to award only women to redress a historic gender imbalance.