Picture the biggest, most jacked kangaroo you've ever seen. Now double it.

That's what was hopping around central Australia tens of thousands of years ago, in landscape that looked much different than the more arid Australia of today.

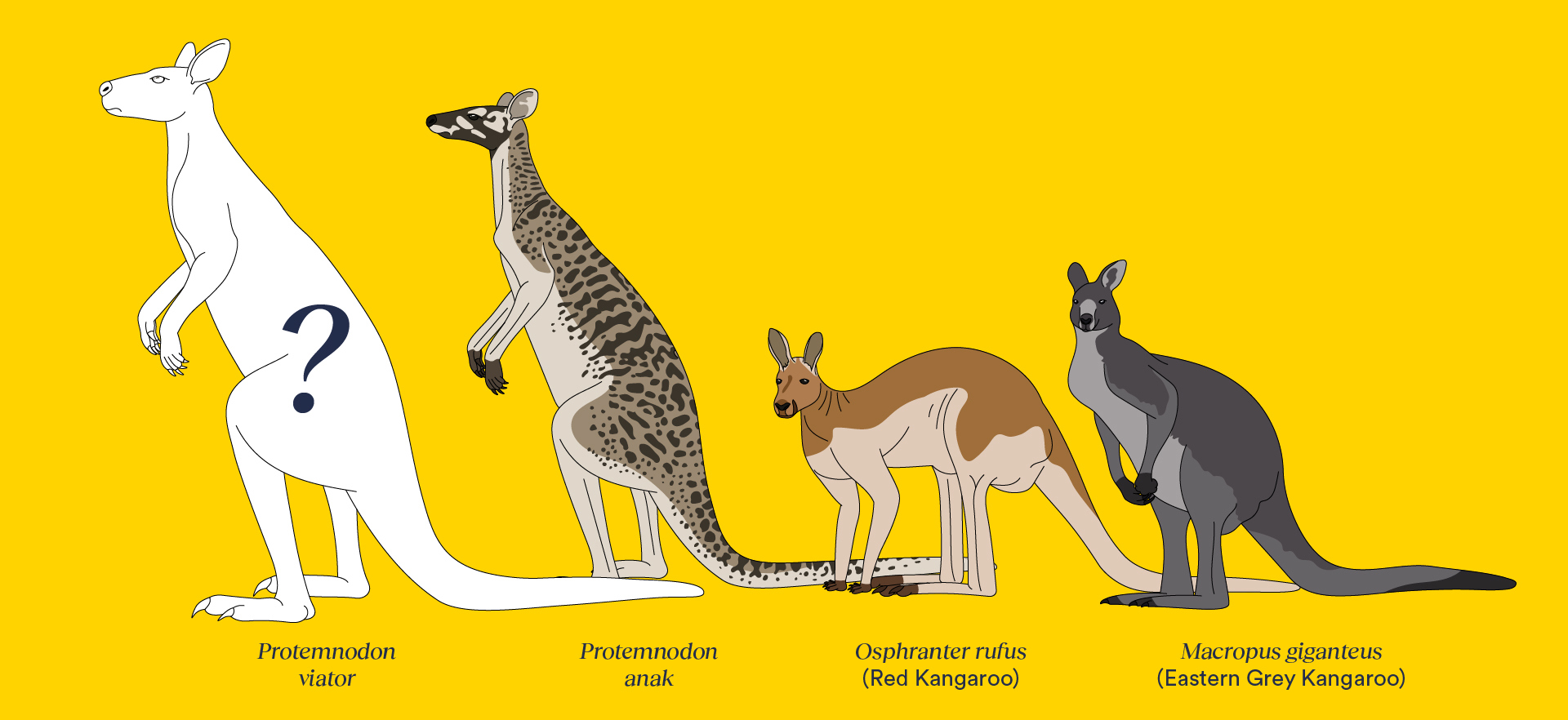

The monster 170-kilogram Protemnodon viator is one of three species newly named in research published today that helps solve a 150-year-old mystery and has possible implications for climate change adaptation.

TIMELINE: How the Bondi Junction Westfield stabbing attack unfolded

Palaeontologist Dr Isaac Kerr said the giant marsupial was about twice the size of the largest red kangaroo living today.

It's among the biggest kangaroo species to be named but can't measure up to the enormous Procoptodon goliah, which could weigh up to 200 kilograms.

Viator, named for the Latin word meaning "traveller" or "wayfarer", was remarkably similar to its still-living descendants in many aspects and well-adapted to its arid central Australian habitat.

But its two other newly named relatives — Protemnodon mamkurra and Protemnodon dawsonae — and other species of the giant kangaroo, could be very different.

Kerr said the key difference was many moved on four legs.

Roos only began hopping between about 5 and 10 million years ago, as Australia became more arid and they needed to move longer distances, more efficiently.

"I think the most interesting thing for me is understanding Australia," the Flinders University researcher said.

"So you grew up around the animals that are still here, and in the Australian bush, and you sort of, you feel like you know this place and you sort of know our animals.

"But for a very long time, it was different to how it is now and that's only a very recent reality for Australia."

READ MORE: What we know about the victims of the Bondi Junction shopping centre stabbing spree

Kerr said research into the species began with renowned British British palaeontologist Sir Richard Owen.

But the naturalist was a bit too focused on the teeth and described too many different species based on small differences.

Kerr said his new research, published today in Megataxa, found the animals were more diverse in shape, range and hopping method than previously thought but also made them easier to tell apart for future research.

While the puzzle of telling apart the various species in the Protemnodon genus, which was so varied some moved on four legs and couldn't even hop, has been solved, the cause of their extinction remains a mystery.

"The first Australians arrived when the first Australians arrived Protemnodon were still alive," Kerr said.

"And then there's this period after humans arrived where Protemnodon start to go extinct."

There was no evidence to suggest Indigenous Australians hunted them but Kerr said it was unclear if their extinction was caused by natural changes to the environment or significant landscape changes caused directly by humans.

The natural climate change was much slower than the human-induced global heating shaping our world now but could help better understand what life on earth is facing.

"You start to be able to use Protemnodon to see how Australia's environments and its animals have changed with climatic changes and different environmental changes over the millennia," Kerr said.

"And that makes them a lot more useful for, particularly with the climate crisis now, for seeing how Australia's fauna are going to react going forward with further changes."

Kerr, Professor Gavin Prideaux and other researchers studied "just about every piece of Protemnodon there is".

They photographed and 3D-scanned more than 800 specimens from 14 museums across four countries in a mammoth five-year effort to identify the species.

"The fossils of this genus are widespread and they're found regularly, but more often than not you have no way of being certain which species you're looking at," Prideaux said, in a statement.

"This study may help researchers feel more confident when working with Protemnodon."

Protemnodon mamkurra was likely a large, thick-boned kangaroo, probably fairly slow-moving and inefficient, and may have only rarely hopped.

Dawsonae was thought to be something like a swamp wallaby.