Despite what the name would suggest, rare diseases are not rare at all, in fact they are "extraordinarily common", clinical geneticist Dr Gareth Bayman says.

There are two million Australians living with a "rare disease", making the term a gigantic misnomer.

In Western Australia alone, there are 63,000 children with a rare disease, a number that would fill Optus Stadium to capacity.

But despite the large numbers of people with a rare disease, getting a diagnosis for these complex, elusive illnesses can often be devastatingly hard.

Children, who are disproportionately affected by rare diseases, can be bounced around from specialist to specialist for years with getting any answers.

This is where Dr Bayman, and the Undiagnosed Diseases Program he heads up at the King Edward Memorial Hospital, comes in.

For the past five years the program has been working to crack some of the state's most unsolvable medical mysteries.

READ MORE: Trisha becomes first Aussie diagnosed with rare disease

The program focusses on children and adolescents transitioning to the adult hospital system, and often takes on the "hardest of the hard" cases yet to be cracked.

"From the start they've been the most challenging cases," Dr Bayman said.

"We have focussed on children who have often had the most torturous journeys and who were just sort of revolving around the hospital seeing lots of different specialists and still not having an answer."

When it began in 2016, the Western Australian program was the first of its kind in Australia. Now, there are undiagnosed diseases programs in NSW, Victoria and Tasmania.

Together, they form Australia's Undiagnosed Diseases Network.

There have been 60 patients who have participated in WA's Undiagnosed Diseases Program since 2016.

Together, its team of 40 specialists have managed to make a diagnosis for 55 per cent of the patients involved.

Although his team was always aiming to solve every case, Dr Bayman said the results had exceeded everyone's initial expectations.

"When we started, we thought we might get an answer for a quarter of the cases," he said.

"Because these are children that have seen lots of people and had lots of tests already. In a way you are dealing with the hardest of the hard."

For patients, having a diagnosis - a name for their illness - could be life changing, Dr Bayman said.

"I think there is enormous power in a diagnosis," he said.

"Often the most important things is removing isolation.

"If you don't have a name for your disease, how do you discuss it with your family, your friends in school? How do you connect to others in a similar situation?"

Having a diagnosis also opened up more treatment options and could help better guide medical care for a patient, he said.

New technology aids quest for answers

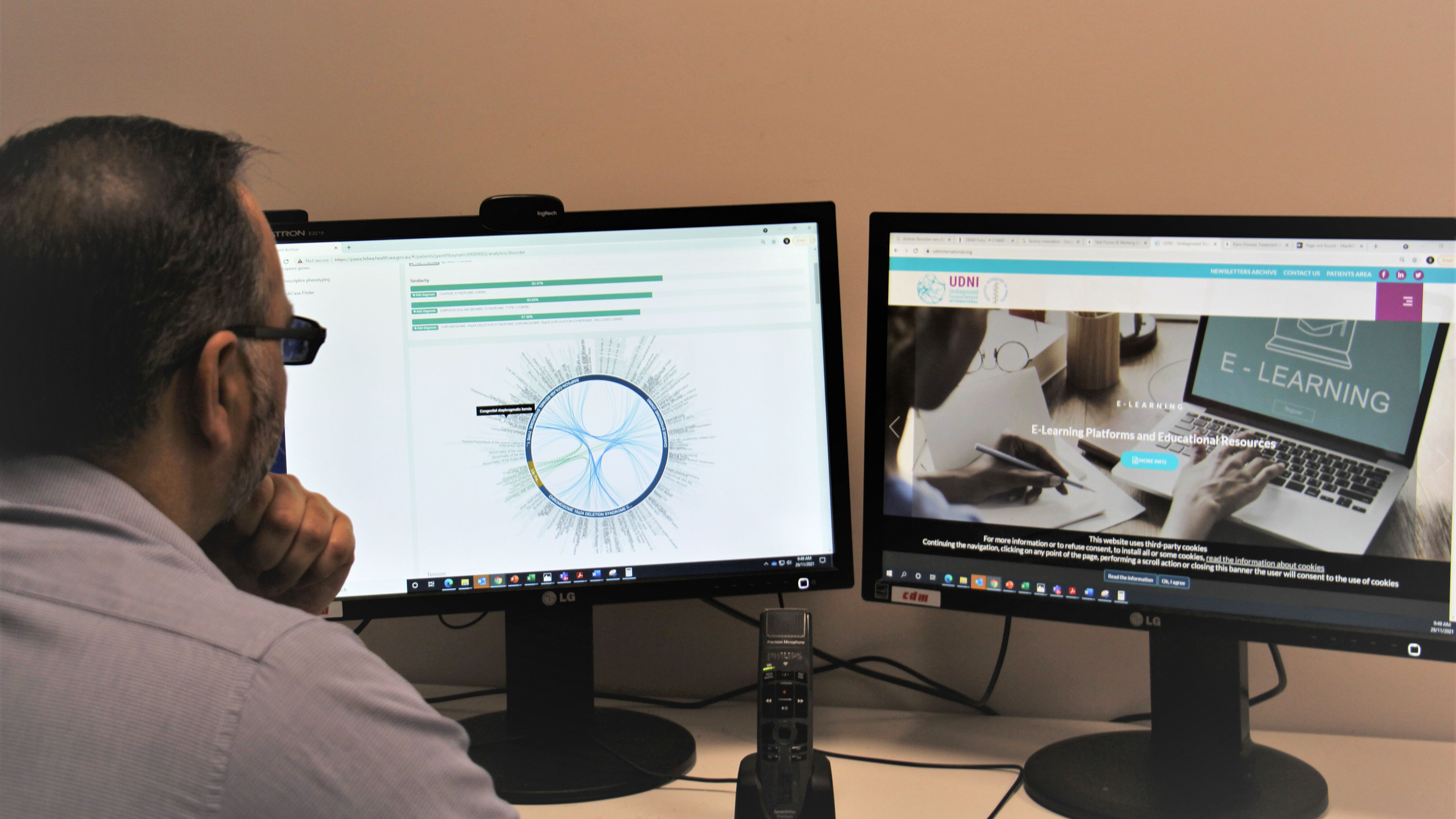

Over the years, new technologies had been added to the team's diagnostic arsenal, Dr Bayman said.

"When we first started doing things, we had genome sequencing, and since then we've added epigenetic testing.

"On top of that, we now have access to further metabolic studies and things like proteomics, so it's a whole range of new technologies that we really focus down to each individual child and their families.

"I guess the bottom line is, we're blending the latest technologies together to get an answer.

"I think that's really exciting because it's sort of cutting-edge science meets leading edge medicine."

International collaboration

The Western Australia Undiagnosed Diseases Program also works closely with an international network of 100 undiagnosed diseases centres scattered across the globe.

In one case, Dr Bayman's team worked with their counterparts in Japan to help solve the case of an Australian girl with an extremely rare illness.

The collaboration led to a new process being developed which allows data to be shared while preserving patient confidentiality. The process is now used in many countries.

"Often, necessity is the mother of invention," Dr Bayman said.

"When you're dealing with really severe conditions, you have to find ways and do things differently.

"You end up creating solutions that can be used far outside of the program itself."

The same could be said for the huge potential medical breakthroughs in rare diseases have to help the rest of the population, he added.

"Some doctors call rare diseases 'fundamental diseases'. The reason they do that is because recurrently we make a discovery in rare diseases that helps everybody else.

"They are so fundamental to the understanding of medicine and how we diagnose, treat and cure diseases."

Contact reporter Emily McPherson at emcpherson@nine.com.au.